In the book Eye Life by Phillip J. Randal are quotes from an essay written in 1938 by a Mrs. S. E. Moore. George VI was king and the Prime Minister was Neville Chamberlain. They give a taste of what village life was like during that year.

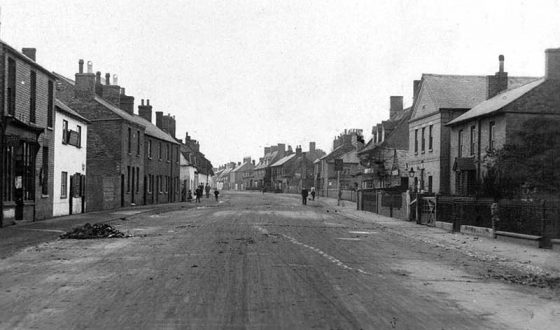

“We who have our roots here remember it as it used to be half a century or more ago-with quaint whitewashed cottages and cobblestones; and with picturesque trees overhanging the front gardens, notably the old ‘conker’ tree near the school, another opposite Luke’s Lane, and the old walnut tree near Stone Villa-old friends and favourites, especially of the schoolchildren. Most of the houses on the north side of the street were covered with vines and their bunches of small green grapes. One house was called The Vinery. Granite covered the roads along which I have seen droves of small ponies, probably going to the Fairs, a performing bear, a German String Band and a herd of goats. Ducks swam through the duckweed on the old pond on Peterborough Road. Beech Lane was quiet, cool, shady and friendly, and Back Lane had but half a dozen cottages with green fields opposite, Bowberry had its row and the usual thatched cottages and cobblestones.

Next to the Manor House lived Mrs. Long the grandmother of Mr. Frank Perkins of diesel fame. Her daughter ran an exclusive bible class for Church of England pupils, while next door at the Manor House the Page family were keen Plymouth Brethren, and sometimes held services in the kitchen.

Old Mrs. Nan Elms, who lived opposite the old Police House, would set off on a summer’s morning in a hired trap, with one or two companions, and some pillowcases, to go cow slipping in the fields Newborough and Dogsthorpe way. I never knew what she did with the cowslips, but for a day or two after, children on the way home from school could be seen in her cottage picking the yellow petals from the flowers. Sheets were spread on the floor and the children were rewarded with home-made butterscotch. The butterscotch was also sold on Sunday to the delight of the children as Sunday trading was then unknown.

Another character was Mr. Parr, a fine old man who kept the stores next to the Red Lion. With his long white beard and skullcap, he was newsagent, postmaster, grocer, draper, dentist (not painless) and chemist-and was well-liked and respected. At the house next to the church high up and cross-legged sat Mr. Ashling the village tailor. I also remember an old lady who received fleeces of wool from the farmers. These were ‘carded’ and spun in her cottage on a large wooden spinning wheel machine and returned to the farmers to be sold for mop-making. The returned balls of thick soft rope were as large as footballs.

Great Aunt Rachel who lived from 1820-1906 was typical of her day and age. Her dresses, made by her, had plain buttoned bodices, very full long skirts, gathered at the sides and back, and a bibless apron, the band fastening on the left side with a large pretty brooch like a button. Her hair was arranged in wings above her ears and curled round them as in early Victorian days, with a broadband, black and tied under her chin with tapes, and a loop that slipped under her small bun. Overall she wore a cap. Her dress and apron colours were figured lilac in the morning, dark figured material in the afternoon and plain good fine black on Sunday. Her three caps were black lace on weekdays but with mauve ribbons on Sunday. When she walked in the garden on damp days she slipped her feet into patterns which resembled strong black patent sandals, but each raised on an iron ring to keep well above the mud and puddles. She wore three-quarter length shawls and carried her large books to church in a black satin bag. She had no teeth and never wore glasses. She made beautiful patchwork quilts and gay fire screens with ruches and rosettes of brightly coloured pleated paper, gummed on a cardboard background in lovely patterns and designs. Her choicest needlework consisted of a set of garments in snow-white linen for her burial. She never possessed a sewing machine. She ate apples very daintily, with a polished bone utensil called a scope, scraping the inside of the apple from the core. My grazed knees were dressed with a concoction of lily leaves and brandy. I tasted honey from the large crimson flowers of her tall cactii which grew in her parlour, and I surreptitiously popped her fuscia buds. She always curtsied to the Vicar.”